VII. Labor Migration

For various reasons, the Banyaremera need cash. The main reason is that the administration has imposed a relatively large-head-tax — 420 francs a year in 1961 — upon every adult male, in order to create the necessary incentive among the peasants to produce cash crops.A man’s tax increases by about 270 francs a year if he has a second wife and, if he has a grown dependent son, by another 420 francs. He may also have a cow, for which he had to pay a cattle-tax of 115 francs a year in 1960.

There are other reasons for wanting cash. These may be divided into three categories:

(1)For buying items from world, markets which are substituted for essentially similar items that had existed in traditional society. These items: hoes, machetes, and clothing are of primary importance.

(2)For buying items of secondary importance that are substituted for like –not essentially similar – objects from traditional society. These are salt, soaps, and European-type beer, The Banyaramera make surprisingly little use of all three items. European-type bees does not have the popularity it seems to have in the rest of Africa. It is bought as a gift to visitors of mark, or as a gift on very especial occasions such as birth, where one bottle might number among the gifts. Two weddings attended by the present writer served no European-type beer although plenty of native bees. The Banyaremera, in general, prefer his or her own banana beer. If given a choice, they take the latter.

(3)To pay for new items such as bicycles, school fees, kerosene, and imported palm oil. There is no evidence to show thatthis last item is a substitution. Therefore, it is treated here as a “new” item.

Coffee alone rarely furnishes a sufficient cash income for these cash expenditures. Therefore, the Banyaremera sell their labor, locally, if they can — but there are few such opportunities — or abroad, usually in Uganda.

Some people living in Remera had jobs with the administration. After the proclamation of the new Republic, all of them lost their jobs and were replaced by others on the Hill. However, the number and the jobs remained essentially the same.

These jobs consist of: one elementary school-teaching post; that of one “policeman” for the sub chieftainship and, later, for the commune; one as secretary to the chieftain and later, to the burgomaster; three posts with the Agricultural Service; one judge-ship; one post of medical assistant; and, one of a road worker.

The position of road worker is the only “permanent” labor job on Remera. Local openings for labor are very few. However, it may be said that while this investigation was in progress, a few laborers were recruited for work on huts that were being constructed in the government post of Kibungu to lodge the refugees from Central Ruanda. A few others were employed to build a communal house in Remera when the new communes came into being. Both of these opportunities were temporary and were due to highly unusual circumstances; opportunities for this sort of odd jobbing did not occur habitually and can be dismissed as a regular source of income.

There is one individual on the Hill who claims to “specialize” in building native houses in exchange for cash. The demand is not sufficient to provide him with much money; although he had finished building a house just prior to the beginning of the investigation, he obtained no other contract for the entire following year.

Possibly the only regular openings for labor would be at the tin mines at Rwinkwavu. When the mine opened about 1940, recruiting was done through the chieftains of the area. They would designate the reluctant ‘volunteers ‘who were required to go to the mine. As has been stated above, Rwinkwavu knew a peak of activity a few years ago, but it has declined markedly with the decrease in the world price of tin. This mine is operated by a European concern and is situated about ten miles north of Remera.

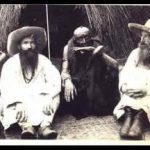

In order to ascertain the degree to which Rwinkwavu is a source of cash among the Banyaremera, a survey was made, which gave the following results: Out of the 64 men questioned, 32 (50%), have never been to work at Rwinkwavu. Of the men questioned, 16 (25% of the total) are Tutsi and only four (25%) of these have worked at Rwinkwavu. Among the 48 Hutu questioned (75% of the total), 28 (or 58.4%) have been to Rwinkwavu to work. The difference between the Tutsi and Hutu is significant. Not only is it improbable that the chieftain would recruit a Tutsi for work in Rwinkwavu, but due to their economic position they have less need of such work, which they consider degrading and below their station.

Twenty of the 32 men who have worked in Rwinkwavu stated the reason for taking work there. Twelve (60%) of these 20 men said they had gone to earn their head-tax. Of the eight others, two had been forcibly “recruited” and, although they did pay their head-tax with the money they earned, their “purpose” in going had not been to earn it; four went to earn money with which to buy clothing; one went to earn money so that he might buy a cow for his bride-price; and one went “to escape the persecutions of the chieftain”.

None of these men stayed more than a few months, except for ten of them who had to sign a contract of a year or more. Overall, it seems that the days of Rwinkwavu’s importance as a source of work opportunity are post. Most of those who have been there are people who had worked there during the period of peak production. As well, as can be determined, there seem to have been only three people from Remera working at Rwinkwavu during the year of investigation. One of these is the ex-laborer on the roads who turned to the mine after he lost his job. The second is a Tutsi from Central Ruanda who came to the dispensary at the mine as a medical assistant and later decided to build his house in Remera. The third individual is the wife of a Munyaremera who is a ‘nurse’ in the same clinic.

However, whether Tutsi or Hutu, the Banyaremera do not like to work in Rwinkwavu; they seem to feel that the work is hard and the pay is low. Moreover, the mining operations are limited and therefore the openings for labor are very few.

In a survey of labor, it was found that nearly all of the informants would state that to obtain money they could work in the fields of other people of Remera in return for a cash sum. Yet upon further analysis, it becomes evident that this too operates as an extension of the reciprocity system, as do the markets and the local “retail trade” discussed above. While, as has been seen, markets redistribute produce, local cultivation for money — like the local “retail trade” — redistributes the cash that comes onto the Hill from labor or coffee.

However, it might happen that a man, in need of cash and not finding it available among his reciprocity group, goes to work in the fields of another Munyaremera with whom he has no reciprocity ties. Here, again, as in “retail trade”, he sells labor to people from whom he expects to buy it, in turn, for the same price at a time when they would be in the same position.

However, there are several persons who bring cash to the Hill regularly and who might pay to have their fields worked without reciprocating themselves. These are the persons holding the government positions previously described. The chieftain and, later the burgomaster, were also paid in cash by the government. The redistribution of money in these two cases, however, was quite different.

The chieftain, being of a traditional chiefly family, was well off to begin with. He also knew how to maintain his position as a redistributor of wealth, and would redistribute his cash among the needy under his jurisdiction andvery likely, within the lineage of which he was the head. He also paid workers to cultivate his fields and had a supervisor of a sort, whom he paid, to direct the work in his fields.

The burgomaster, on the other hand, was a poor Hutu who did not understand the roles associated with chieftainship nor had he a clear view of his own quite novel position. His redistributions were, therefore, apparently limited to buying European-type beer from one of the local incipient merchants as part of an effort to win the Banyaremera to his party. The author was unable to ascertain how and where the burgomaster obtained his foodstuff, as he had no land on Remera.

Therefore, it might be concluded that overall, cultivation for cash, at the local level, seemed to function as a means of redistributing cash rather than as an adjunct to capital accumulation.

WORK ABROAD

Not having enough local openings, the Munyaremera exports his labor when he feels the need for cash. He might go to Buhaya, in Tanganyika, but this happens seldom. Not so with the people of Gitara, a small refuge community about 6.5 miles east of Remera as the crow flies. Gitara is very much isolated from the surrounding areas but perhaps a bit less isolated from the nearly deserted eastern border of Ruanda. Therefore, the people of Gitara go to Buhaya rather than Uganda. They go on foot. Usually, the Munyaremera goes to Uganda, which is easier of access, although much farther. He leaves his wife, children and perhaps his brothers to take care of his fields until he returns. These people are always able to produce their own subsistence, which allows the migrant to save his wages, except for the money that he has to spend on route and, sometimes, for living abroad

https://uk.amateka.net/vii-labor-migration/https://uk.amateka.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/map_rwanda-urundi.pnghttps://uk.amateka.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/map_rwanda-urundi-150x150.pngModel CitizenshipFor various reasons, the Banyaremera need cash. The main reason is that the administration has imposed a relatively large-head-tax — 420 francs a year in 1961 — upon every adult male, in order to create the necessary incentive among the peasants to produce cash crops.A man's tax increases by...BarataBarata rpierre@ikaze.netAdministratorAMATEKA | HISTORY OF RWANDA