Kinyaga And The Kivu Complex

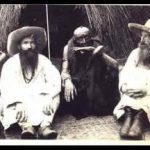

As we have seen, two decades of German presence in Rwanda substantially altered the political processes and the dynamics of clientship. After the Belgian victory in World War I, the new Belgian administration concentrated on consolidating political power; from the mid-1920s they strove to streamline and organize the administrative system based on rule by Tuutsi chiefs. This process brought about a substantial increase in the demands that chiefs were required to (and were able to) make on the population at large. Increasingly these demands, and the larger process of which they were a part, had a corrosive effect on patron–client bonds. Belgian authorities attempted to “humanize” and “civilize” the rule of Tuutsi chiefs -they hoped to maintain the system by sanitizing it, by removing the “abuses.” The problem was, of course, that such abuses were central to the way the system of chiefly rule functioned; they were not occasional aberrations, products of individual moral “lapses.” In fact, as the Belgian administration recognized, harsh conditions in the rural areas served other, economic goals of the colonial state -such as producing food surpluses or cash crops for export, or “motivating” people to work for wages as a means of escaping multiple exactions in their rural communities.

The problem of establishing a viable colonial order was not, of course, a question of administrative structure alone. In Rwanda, as elsewhere in Africa, colonial statebuilding was propelled and shaped by economic concerns. Colonialism served as a vehicle for the introduction of a type of dependent capitalism. And administrative power in the colonial state was used to create one of the essential features of capitalist social formations -a class of people who Iacked secure access to the basic means of production (in this case the land). The economic transformations

accompanying this -in markets, commercial networks, crops cultivated, and in the social relations of production-are important for understanding the demands made by the Belgian administration on Rwandan chiefs, and the exploitative goals for which chiefs used their power. In Rwanda generally, the economic policies of the colonial state -often themselves contradictory-contributed to the contradictory nature and impact of chiefly rule, and fostered the growth of political consciousness among rural dwellers. This chapter will outline some of the major features of Belgian economic policies toward Rwanda, and, more broadly, toward the combined administrative entity of Ruanda-Urundi -a very small, resource-poor colony adjacent to (and administered as a part of) the Belgian Congo. The discussion will then explore the particular ramifications of Belgian economic policies and the system of labor control which developed at the local level in Kinyaga.