The Division Of Labor

The great majority of the Banyaremera follow the peasant’s daily routine. The workday in the field is rather short by our standards. It begins at 7:00 A.M. and ends at noon. The afternoon is given to “visiting”, a strict social obligation that has its proper function. However, when time presses for sowing or harvesting, some individuals might work in the fields during the afternoon.

Both men and women work in the fields, but as the household head is responsible for the household’s relationships to the rest of the community, including that to the chieftain, he is often absent and the wife is left, in the long run, with the largest care of the fields, i.e, the weeding.

The land breaking is done with hoes and executed in groups including at least one family and often neighborhood groups of several men and their wives. The men do seeding, although women might plant slips of sweet potatoes. All, including the children, do harvesting.

Women take care of the household and the children. They sweep the house and yard and prepare meals. They take care of the stores of food and fetch the sweet potatoes and manioc directly from the fields. They make the finer baskets and the mats. They fetch the grasses that go under the mat for the bed, and those that are intended for the cows.

Men do the heavier work, such as building houses, granaries, and enclosures, and keeping them in repair; fetching firewood and clearing bush when necessary. They weave the larger storage baskets. Generally, the men fetch the water and bunches of bananas necessary for beer making and they make the beer. The men also take care of the cattle, pats, and sheep. Not so long ago, the men had to serve their patron, their chieftain, and the administration with various labors and tasks, which took a surprising amount of their time. “Paying court to be seen” by the proper persons counts as much as subsistence itself.

The children from six to ten years of age help in keeping the goats and in fetching water. They begin tohelp in the fields and carry things on their heads at an early age. ‘They run errands.

There are craftsmen of a sort in Remera, but certainly none of them makes a living at their craft. There is a lineage of blacksmiths who have not plied their trade since the grandfather died several years ago. There is the odd individual who might let it be known that he likes to build houses in return for a fee. There is also one individual who has learned — on his own to make chairs. Once in a while, he takes time off to make one and sell it. Only the potters regularly make pots and pipes for sale, but even this household gives half of its time to agriculture.

Most households are materially self-sufficient, except for hoes, machetes, clothing, and pots; they can weave their own baskets and mats and build their own houses.

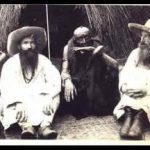

The difference between classes is mostly a difference in emphasis. The richer Tutsi do less work in the fields and more herding; they spend more time “paying court” and carrying on sundry intrigues.

AGRICULTURE

Agricultural production seems to have been very low in traditional times. The soils of Ruanda are poor and the plan Décennal depicts a dismal picture of them and the possibility of reclaiming them.In addition, the rains have always been very irregular and unpredictable. The social system does not encourage production and prevents the peasants from using the land to the full. It is often said, for example, that because of the need for dry season pastures, the Tutsi forbade the peasants to use the floor of the marshes for agricultural purposes. Moreover, the only non-seasonal crops of importance are the plantain banana and sweet potatoes. The former produces little between February and April or May.

Famines were frequent in the past, and much of the effort of the Belgian administration was concentrated on improving production. Non-seasonal crops such as manioc and sweet potatoes were introduced and regulations made their cultivation compulsory. Other regulations imposed the use of the bottom marshlands for agricultural purposes. Innovations such as the cultivation of soya beans and terracing of cultivated slopes were unsuccessful in and about Remera. The last famine occurred in 1943 and, since then the people of Remera seem to have always produced enough to provide for their subsistence.

There are two growing seasons in Remera. They cannot, however, be delimited sharply because of the irregularity of the rains. Theoretically, the primary and longest growing season extends from February or January to May or June. It is calledicyi, impeshi, or impagasha; Planting may begin at the end of January, if the season is early, but it can be Match before any planting is done, if the season is late. The secondary, short season, extends from September to December and January. It is called urugarigi (or urugaryi). The fruits of the important impishi harvest have to lest through the dry season and the secondary growing season, so that the impishi harvest has to be the more abundant. It is also the more diversified harvest. The season can be late and begin in October instead of September and be harvested at the endof January.

The staple crop in Remera is the plantain banana. It is followed closely in importance by beans. These two crops account for the largest part of the agricultural production. Third, in importance is the sweet potato; fourth in sorghum, which has replaced eleusine (finger millet) as a crop; fifth are peas and maize. Other subsidiary crops such as squash, groundnuts — another new product, which did not become very popular, but did not disappear entirely from the scene as did the soya bean — tobacco, potatoes, onions, cabbages, and sunflowers are also cultivated, along with a number of relish plants which are cultivated only incidentally around the rugo. In addition to these, a few kind of fruit have been introduced as potential cash crops but their out-put is, in fact insignificant in Remera; these consist of oranges, avocados, papaya, pineapples, and tomatoes. (One man on Remera had just planted a few orange trees that were not yet productive; another had two papaya and a few pineapple plants; a third had some thirty-pineapple plants; while the ex-chieftain had a plantation of some still unproductive avocado trees.) Such fruit is only grown sporadically. No reliable market is found for the produce so that it is eaten, more often than not, by the produce. Lastly is manioc, introduced by the Belgian administration to stave off famines, but used beyond that limit by the poorer segment of the population.

The universal tool for cultivation is the hoe. Each household has four or five hoes in different stages of wear. (One hoe might last three or four years. A new one is called isuka, and a worn one is called ifuni.) If thick bush and brush has to be cut, another generalized instrument — the machete — is used.

In preparation for planting, the ground is hoed some eight inches in depth and if any weeds have overgrown the area, theseare hoed under. If the weeds are not too hardy, they are left as green fertilizer. Crab grass is left to dry with roots up and a few days later it is picked up and burned; the ashes are used as fertilizer. Manure from cows or pats is in no way systematically used for fertilization. When cattle graze in a field, or when they graze upon the stubble of sorghum, they fertilize the fields accidently in the sense that the herder leaves the droppings there. The uncultivable pasturelands and the cow paths get more than their share. (The droppings from the kraal are used as mortar for walls and in surfacing the inside of certain baskets.) However, nothing else is done to the ground before it is planted, and nothing at all is done to a field that has just been harvested. Just as the weeds start to grow, again the next crop is planted.

Beans and sorghum are sownbroadcast, but not in the horizontal sweeping gesture as we are accustomed to think of as “broadcast”; the movement is an overhead throw, ending in a downward movement of the wrist that scatters the beans or sorghum on the ground. The sown fields are periodically weeded.

https://uk.amateka.net/the-division-of-labor/https://uk.amateka.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/agriculture.jpghttps://uk.amateka.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/agriculture-150x150.jpgModel CitizenshipThe great majority of the Banyaremera follow the peasant's daily routine. The workday in the field is rather short by our standards. It begins at 7:00 A.M. and ends at noon. The afternoon is given to 'visiting', a strict social obligation that has its proper function. However, when time...BarataBarata rpierre@ikaze.netAdministratorAMATEKA | HISTORY OF RWANDA